The normal procedure for arms export licences in the Netherlands is that export officials decide whether to grant one or not, following a standard procedure, including a criteria check relating to e.g. human rights, internal and regional tensions and sustainable development. Only after the licence has been granted (or rejected), the Parliament has a role. As controller of the government it can then give its opinion on whether the criteria were implemented correctly. Occasionally, at the special request of the Parliament, upcoming deals are discussed with the government beforehand, but it is for the government to take the final decision.

Therefore, in aftermath of the failed attempt by the Dutch Ministry of Defence (MoD) to sell surplus Leopard tanks to Indonesia, many journalists logically assumed that the MoD could have ignored the negative position of the Dutch Parliament with respect to the intended export. But they were mistaken: with the export of surplus military sales, the role of the parliament in the Netherlands is much stronger.

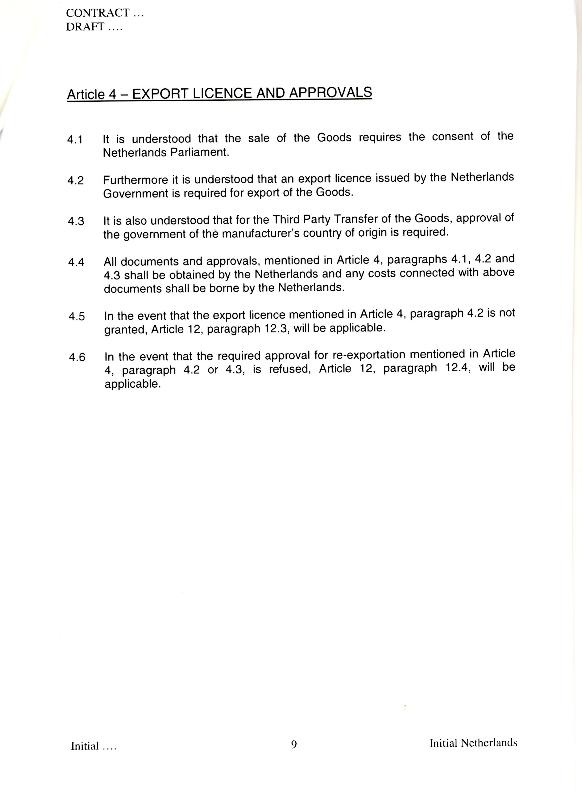

Through a request under the Dutch Freedom of Information Act, the Campagne tegen Wapenhandel last week obtained a standard contract that the MoD uses for selling surplus weapons.

Under article 4 “Export licence and approvals” it reads: “4.1 It is understood that the sale of the Goods requires the consent of the Netherlands Parliament.” As simple as that. Also, under 12.3 it says that “the Contract will be terminated if the consent or export licence […] is not granted”.

Therefore logically, MP Arjan El Fassed – who has taken on the issue since we first reported on it in November 2011 – this week filed a set of questions to the government, demanding clarity about how the government is dealing with Parliament’s say in surplus sales.

El Fassed is asking why the government did not terminate negotiations after a large majority in Parliament voted against a potential sale, as late as in December 2011, specifically because of human rights concerns.

And why the government has not issued a so-called denial-notification to its EU colleagues – a confidence building mechanism aimed at preventing ‘undercutting’ by fellow member states of an export licence denied by another state. Prevention of undercutting actually was the main export control policy commitment of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 2011.

Such a denial notification would have affected Leopard negotiations that are reportedly ongoing between Germany and Indonesia since a Dutch deal appeared close to impossible.

Meanwhile, also in Berlin opposition against the tank deal is mounting, including objections from the largest opposition party, the social-democratic SPD, as well as the Left party and the Greens.

So we will see how harmonised and coherent European arms export control efforts are, 14 years after the first serious steps in that direction.

[FS, 18 July 2012]