Guest Blog by Andreas Weibel – Gruppe für eine Schweiz ohne Armee GSoA (Group for Switzerland Without an Army)

Switzerland is one of the few Western nations that have not provided any arms to Ukraine. Moreover, the country has annoyed or even angered friendly governments by not granting any permission to re-export weaponry to Ukraine, which Swiss companies had sold them decades ago. While a fierce debate about re-exports is ongoing, there is a broad consensus among Swiss politicians not to allow direct exports to Ukraine. This article sheds some light on the historical, legal and political reasons why the discussion on the issue is different in Switzerland than in most European countries.

Two Faces of a Nation

Switzerland may have a reputation as a peaceful nation. There is some truth to that: The neutral alpine republic has not seen war for almost two centuries, it hosted numerous peace negotiations and diplomatic initiatives, and it is the birth place of the Red Cross and the Geneva Conventions.

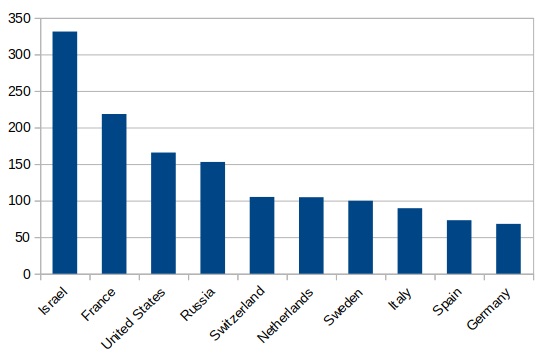

Yet, there is a darker, militaristic side to this country. Switzerland has one of the largest armies in Europe by almost any measure. The country not only upholds universal conscription for men. Mandatory military service might be extended to women. Another part of this dark side is a sizeable arms export industry. Per capita, only four counties exported more arms than Switzerland between 2018 and 2022. The main export products include air defence systems, armoured personnel carriers, training aircraft, and all kinds of ammunition.

Arms exports per capita, 2018 to 2022. Data: SIPRI. Figure: GSoA

Neutrality

Swiss historians love to argue about when the Swiss Confederation started to become a neutral state and what function that neutrality had at that time. Conservatives trace the roots of Swiss neutrality back to the bitter defeat of the old Swiss cantons at the battle of Marignano in 1515 that allegedly taught the Swiss to stay out of great power politics and not to interfere in foreign wars. Others argue that neutrality was imposed upon the Swiss in the Congress of Vienna to create a buffer state between France and Austria. At any rate, neutrality has become an integral part of Swiss identity, especially during and after the Second World War. Neutrality, at that time, became a common value around which the people of all parts, of all languages and all religions of the country could rally.

Polls before the Ukraine war showed 95% support for neutrality amongst the Swiss population. This support dropped only slightly to 91% by the most recent poll in spring 2023. The broad acceptance of neutrality can also be explained by the fact that different political groups have entirely different interpretations and motivations of neutrality: Right-wing conservatives consider neutrality as a tool for isolationism and separation from Europe. Others see neutrality as a strategy for national security that has served us well for two centuries. And others again praise the humanitarian or even pacifist aspect of neutrality that allows Switzerland to stay out of wars and help conflict parties to negotiate.

International Law

While there are very different views of what neutrality actually entails within Switzerland, its definition in international law is clear and well-defined by the Hague Conventions of 1907. With regard to arms exports, the Treaty specifies that “Every measure of restriction or prohibition taken by a neutral Power in regard to [arms exports] must be impartially applied by it to both belligerents.”

It is important to note that the Hague Conventions only apply to armed conflicts between nation states, but not to internal conflicts. Because interstate wars have been rare in recent years, these regulations have hardly ever been applied. Switzerland, for example, had no qualms about supplying arms to Saudi Arabia for a long time, as the conflict in Yemen was classified as an internal conflict with international participation.

Domestic Law

The Swiss political system is peculiar and complex and arms export politics is particularly muddled. But to understand the current discussions, it helps to know the back story of the last decade and a half.

In 2009, the Swiss electorate rejected a popular initiative (see below) by the anti-militarist Group for Switzerland without an Army (GSoA) to amend the constitution with a total ban on arms export. In the lead-up to the vote, the government changed the export regulations with a criterion that excluded all arms exports to “countries involved in an international or internal armed conflict”. The goal of this revision was to reassure to population that Switzerland already has strict export rules for arms, and that there is no need to vote in favour of a radical initiative.

Voting poster: Switzerland has better things to export than tanks.

Apparently, the government was not aware of the legal meaning of these words – armed conflicts are a key concept of humanitarian law and therefore sufficiently well-defined. At that time, all major customers were obviously involved in an armed conflict in one way or the other, be it in Iraq or Afghanistan. To this day, it is unclear how this blunder happened, but since then, the error has shaped the debate on arms exports. There are no legal means to challenge export licenses in court, so that the government could continue to issue export licences at its discretion. But the government became increasingly bogged down in legal contradictions in its arguments. Especially after Saudi Arabia entered the war in Yemen, the government felt obliged to restrict exports to the kingdom.

In turn, in 2017, the arms industry approached the defence committees of the parliament with an official letter, asking to change the regulations again, in order to “create regulatory lances of equal length” as European competitors. Both parliament and government responded favourably to these demands and drafted amendments to the regulations that would have allowed to allow exports to countries involved in an internal armed conflict “if there is no reason to assume that the respective military goods will actually be used in that conflict”.

This did not go down well with the public at all. The cynicism of the proposals was evidently too obvious. The public outcry was so fierce that the government and parliament had to withdraw the propositions. Moreover, in a direct-democratic move of political jiu-jitsu, GSoA and other organisations and parties started another popular initiative called “Initiative against arms exports to civil wars”, which would have raised the current regulations from the ordinance level to the constitutional level.

The necessary signatures were collected rapidly and in 2021, the organisations agree to a compromise. Since then, the export criteria – including the ban on exports to countries involved in an armed conflict – are codified at the legislative level. This means that only the parliament (not the government) can change the criteria and any changes can be challenged be a popular referendum. Since then, the government still grants export licences to countries like the United States – that obviously are involved in an armed conflict in one way or the other – but no new licenses were granted to Saudi Arabia.

Reactions to the War Against Ukraine

Public sympathies regarding the war in Ukraine are quite clear in Switzerland. Ukraine’s right to self-defence is universally recognised. Only a small group of right-wing politicians and a few radicalised by the Corona pandemic understand Putin’s war of aggression. Unlike in Germany, for example, even in the peace movement only a minority subscribes to calls for appeasement.

At the beginning of the war, when the government hesitated to accept the economic sanctions imposed by the European Union, large protests brought tens of thousands onto the streets. The government’s subsequent concession was partly described by the international media as a departure from traditional neutrality. That was a misunderstanding insofar as economic sanctions are not restricted by the law of neutrality.

Proposed Changes to Export Regulations

It’s no surprise that the arms industry is keen to use the current situation to reverse the changes introduced in 2021. In recent months, there have been a multitude of parliamentary motions – so many that even those involved in the parliamentary discussions struggle to keep track.

- Get rid of all end user certificates – that would allow friendly nations to re-export Swiss arms to Ukraine. But it would obviously also allow Swiss exports to Saudi Arabia again via an intermediary, e.g. in the UK.

- Add a new loophole that would allow the government to override all export criteria if the national security of Switzerland is at stake – the reasoning behind this motion is that it can be argued that a thriving defence industry is a prerequisite for our national defence, and a thriving defence industry requires as many exports as possible.

- Allow re-exports of Swiss arms under very specific circumstances, in particular if there is a two-third majority in the United Nations General Assembly the condemns an armed attack – This is a legally intricate attempt to reconcile the law of neutrality with the aim to allow re-exports only to Ukraine.

At the moment, the outcome is very hard to predict, as all political camps are divided within:

- The isolationist right favours a strong arms industry, but is opposed to any arms exports to Ukraine, be it directly or indirectly.

- The left would like to support Ukraine, but it is reluctant to allow re-exports and certainly does not want to loosen export regulations to other countries.

- The political centre’s goal is to position Switzerland as a reliable partner, but it might not want to compromise with left in order not to miss an opportunity to loosen export regulations in general.

Swiss weapons will not turn the tide of the war. However, the discussions about arms exports divert attention away from issues where Switzerland could and should have a much more immediate impact, like humanitarian aid, sanctions on energy trade and support for Russian dissidents and deserters.